|

Illustration of a lone stellar-mass black hole.

(FECYT, IAC) |

The first detection of what appears to be a rogue black hole drifting through the Milky Way, revealed earlier this year, just got important validation.

A second team of scientists, conducting a separate,

independent analysis, has reached almost the same finding, adding weight to the

idea that we've potentially identified a rogue black hole wandering the galaxy.

Led by astronomers Casey Lam and Jessica Lu of the

University of California, Berkeley, the new work has arrived at a slightly

different conclusion, however. Given the mass range of the object, it could be

a neutron star, rather than a black hole, according to the new study.

Either way, though, this means that we may have a new

tool for searching for 'dark', compact objects that are otherwise undetectable

in our galaxy, by measuring the way their gravitational fields warp and distort

the light of distant stars as they pass in front of them, called gravitational

microlensing.

"This is the first free-floating black hole or

neutron star discovered with gravitational microlensing," Lu says.

"With microlensing, we're able to probe these

lonely, compact objects and weigh them. I think we have opened a new window

onto these dark objects, which can't be seen any other way."

Black holes are theorized to be the collapsed cores of

massive stars that have reached the ends of their lives and ejected their outer

material. Such black hole precursor stars – bigger than 30 times the mass of

the Sun – are thought to live relatively short lives.

According to our best estimates, therefore, there

should be as many as 10 million to 1 billion stellar-mass black holes out

there, drifting peacefully and quietly through the galaxy.

But black holes are called black holes for a reason.

They emit no light that we can detect, unless material is falling onto them, a

process that generates X-rays from the space around the black hole. So if a

black hole is just hanging out, doing nothing, we have almost no way of

detecting it.

Almost. What a black hole does have is an extreme

gravitational field, so powerful that it warps any light that travels through

it. For us, as observers, that means we might see a distant star appear

brighter, and in a different position, than how it appears normally.

On 2 June 2011, that's exactly what happened. Two

separate microlensing surveys – the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment

(OGLE) and Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA) – independently

recorded an event that ended up peaking on July 20.

This event was named MOA-2011-BLG-191/OGLE-2011-BLG-0462

(shortened to OB110462), and because it was unusually long and unusually

bright, scientists homed in for a closer look.

"How long the brightening event lasts is a hint

of how massive the foreground lens bending the light of the background star

is," Lam explains.

"Long events are more likely due to black holes.

It's not a guarantee, though, because the duration of the brightening episode

not only depends on how massive the foreground lens is, but also on how fast

the foreground lens and background star are moving relative to each other.

"However, by also getting measurements of the

apparent position of the background star, we can confirm whether the foreground

lens really is a black hole."

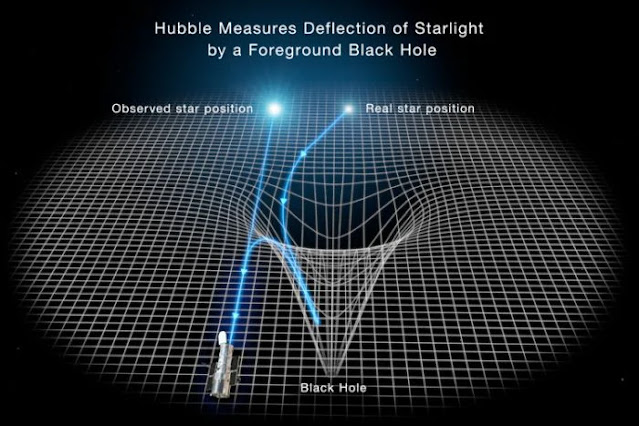

Illustration showing how Hubble views a microlensing

event. (NASA, ESA, STScI, Joseph Olmsted) |

In this case, observations of the region were taken on

eight separate occasions using the Hubble Space Telescope, up until 2017.

From a deep analysis of this data, a team of

astronomers led by Kailash Sahu of the Space Telescope Science Institute

concluded that the culprit was a microlensing black hole clocking in at 7.1

times the mass of the Sun, at a distance of 5,153 light-years away.

Lu and Lam's analysis now adds more data from Hubble,

as recently captured as 2021. Their team found that the object is somewhat

smaller, between 1.6 and 4.4 times the mass of the Sun.

This means that the object could be a neutron star.

That's also the collapsed core of a massive star, one that started out between

8 and 30 times the mass of the Sun.

The resulting object is supported by something called

neutron degeneracy pressure, whereby neutrons don't want to occupy the same

space; this prevents it from completely collapsing into a black hole. Such an

object has a mass limit of around 2.4 times the mass of the Sun.

Interestingly, no black holes have been detected below

around 5 times the mass of the Sun. This is referred to as the lower mass gap.

If the work of Lam and her colleagues is correct, that means we could have the

detection of a lower mass gap object on our hands, which is very tantalizing.

The two teams came back with different masses for the

lensing object because their analyses returned different results for the

relative motions of the compact object and the lensed star.

Sahu and his team found that the compact object is

moving at a relatively high velocity of 45 kilometers per second, as the result

of a natal kick: a lopsided supernova explosion can send the collapsed core

speeding away.

Lam and her colleagues got 30 kilometers per second,

however. This result, they say, suggests that perhaps a supernova explosion is

not necessary for the birth of a black hole.

Right now, it's impossible to draw a firm conclusion

from OB110462 about which estimate is correct, but astronomers expect to learn

a lot from the discovery of more of these objects in the future.

"Whatever it is, the object is the first dark

stellar remnant discovered wandering through the galaxy unaccompanied by

another star," Lam says.

Reference: ArXiv

0 Comments